Caro Jost – Action requirements

Caro Jost often traces the past of others in her work. The archives of well-known artists, pictures of their studios or even their material bills become objects in Jost’s works. In her ongoing series of Streetprints, too, it is traces of what has been, inscribed in public places, to which she gives a body. Marginal histories and memories play a central role. She appropriates things that seem ephemeral, for the most part perhaps they are, giving the incidental a physicality without being nostalgic or worshipful. Rather, it is her way of listening and looking closely that characterizes her engagement with the objects. This creates conversations that contain Jost’s reflection, but also testify to the material’s resistance.

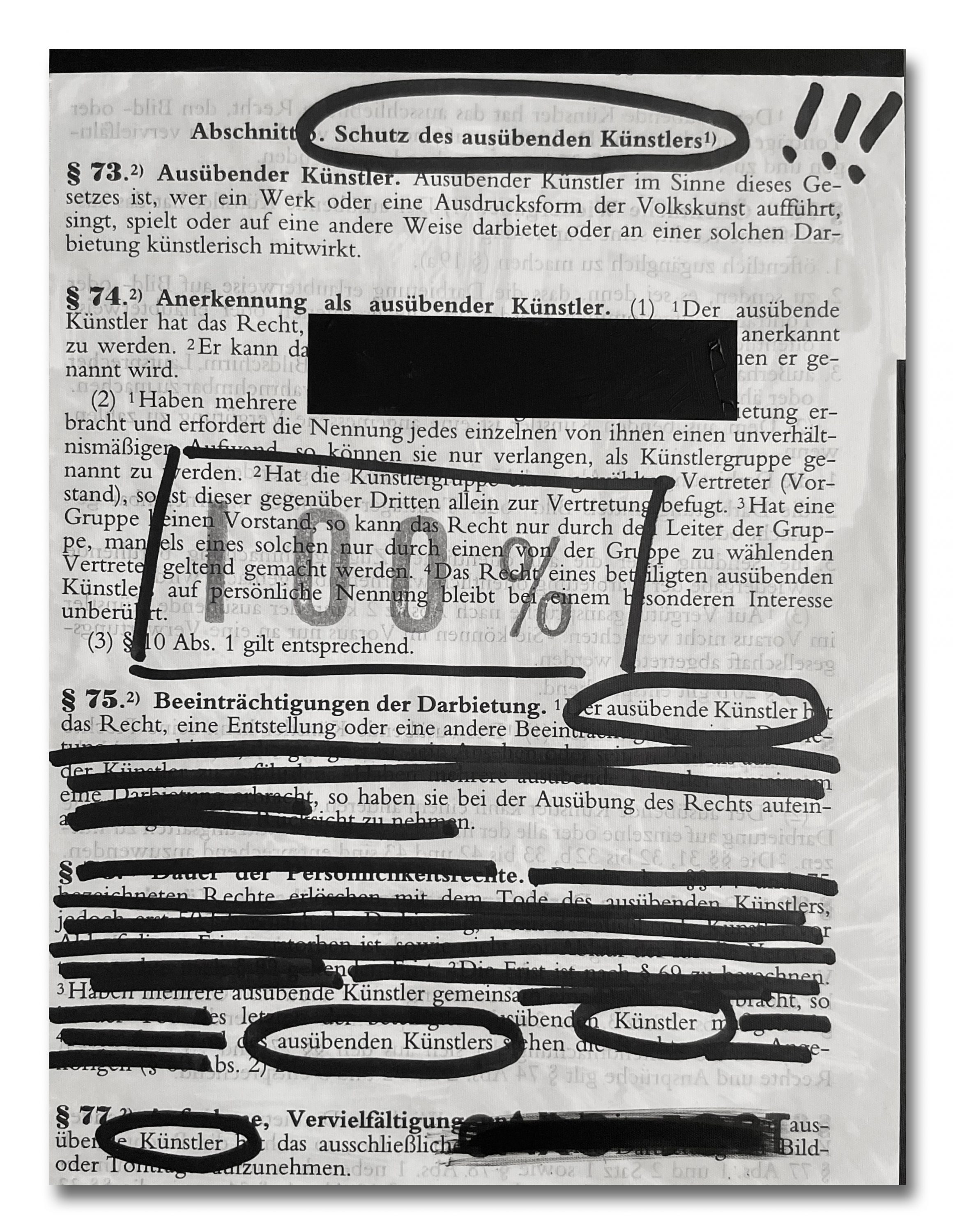

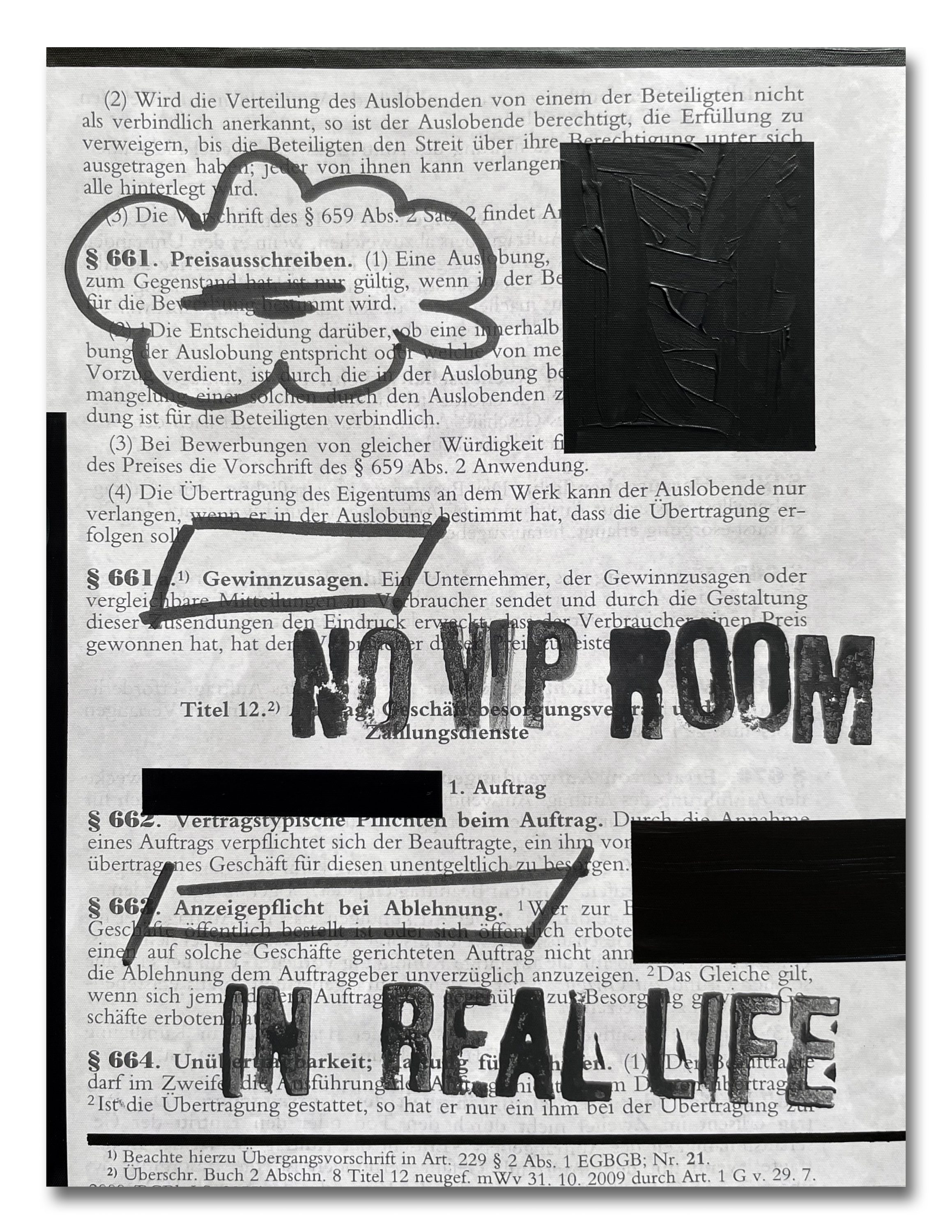

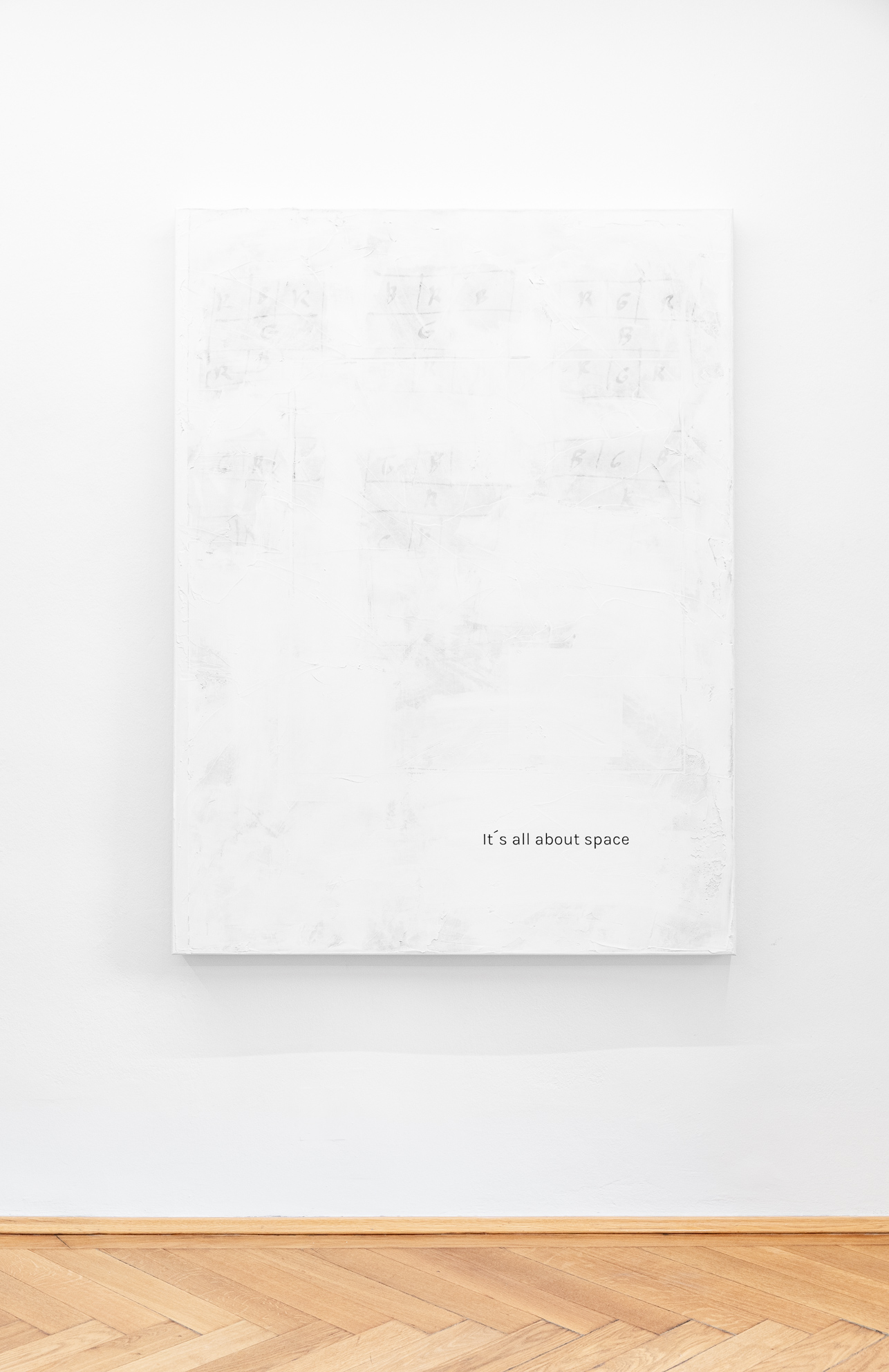

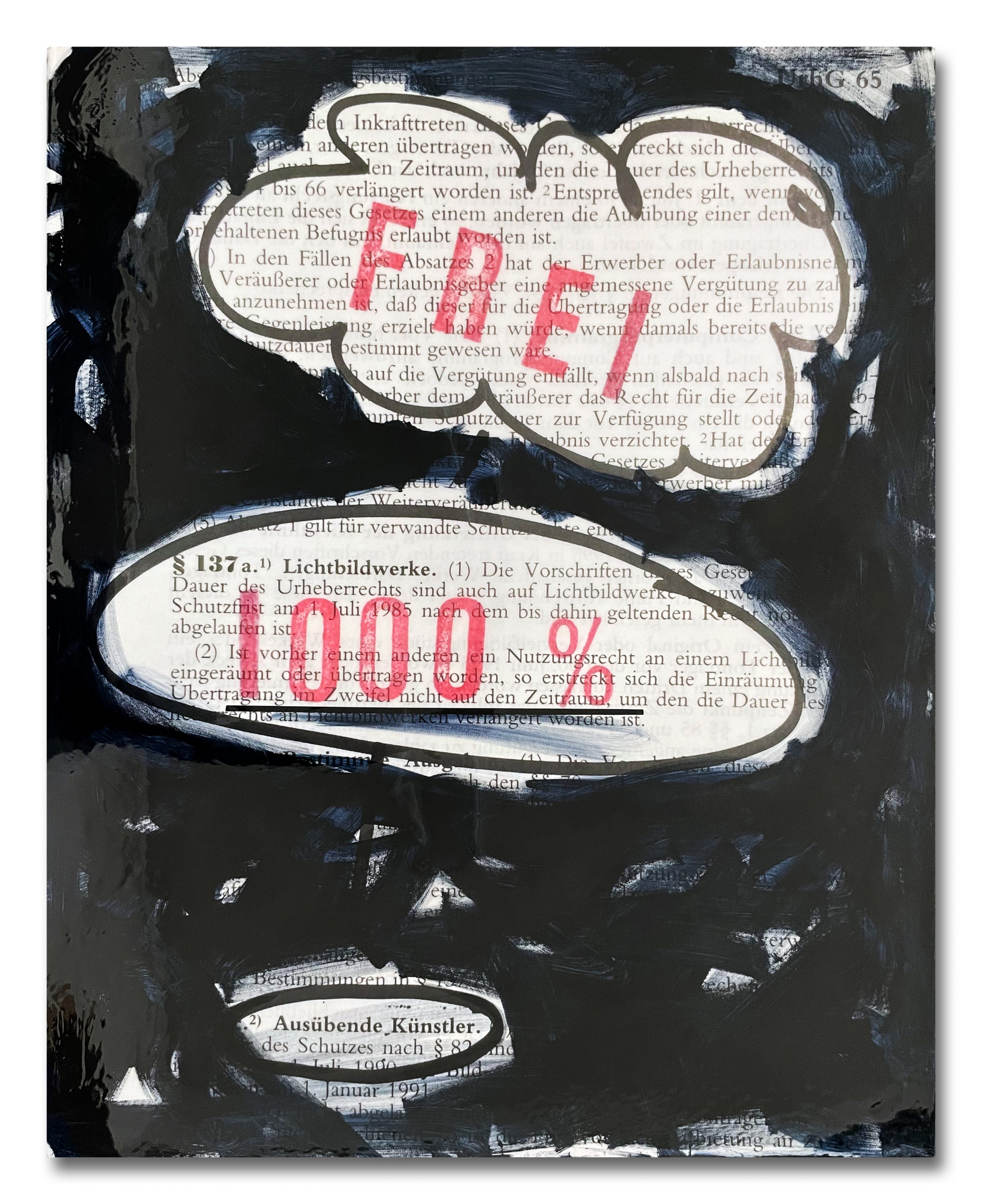

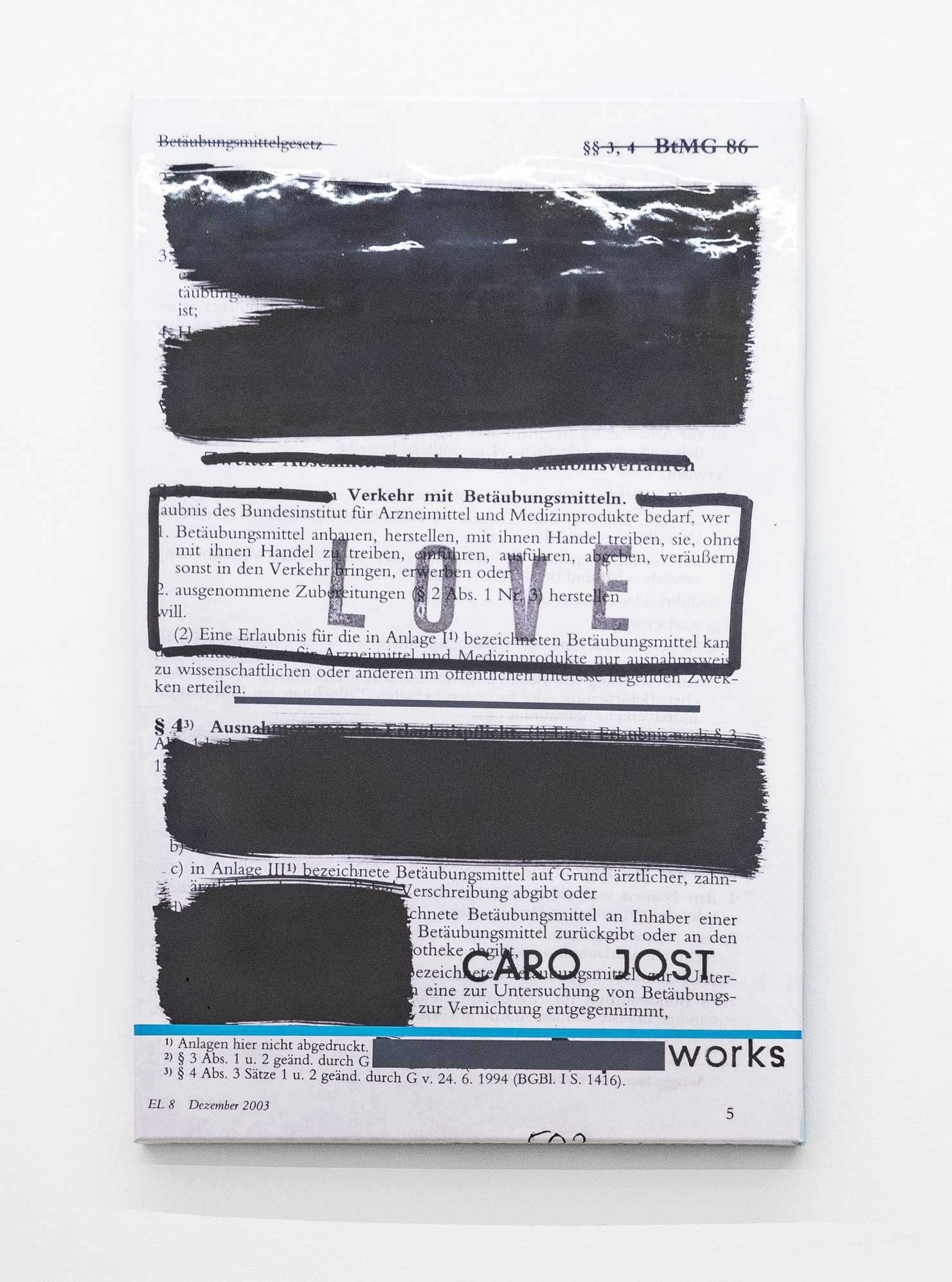

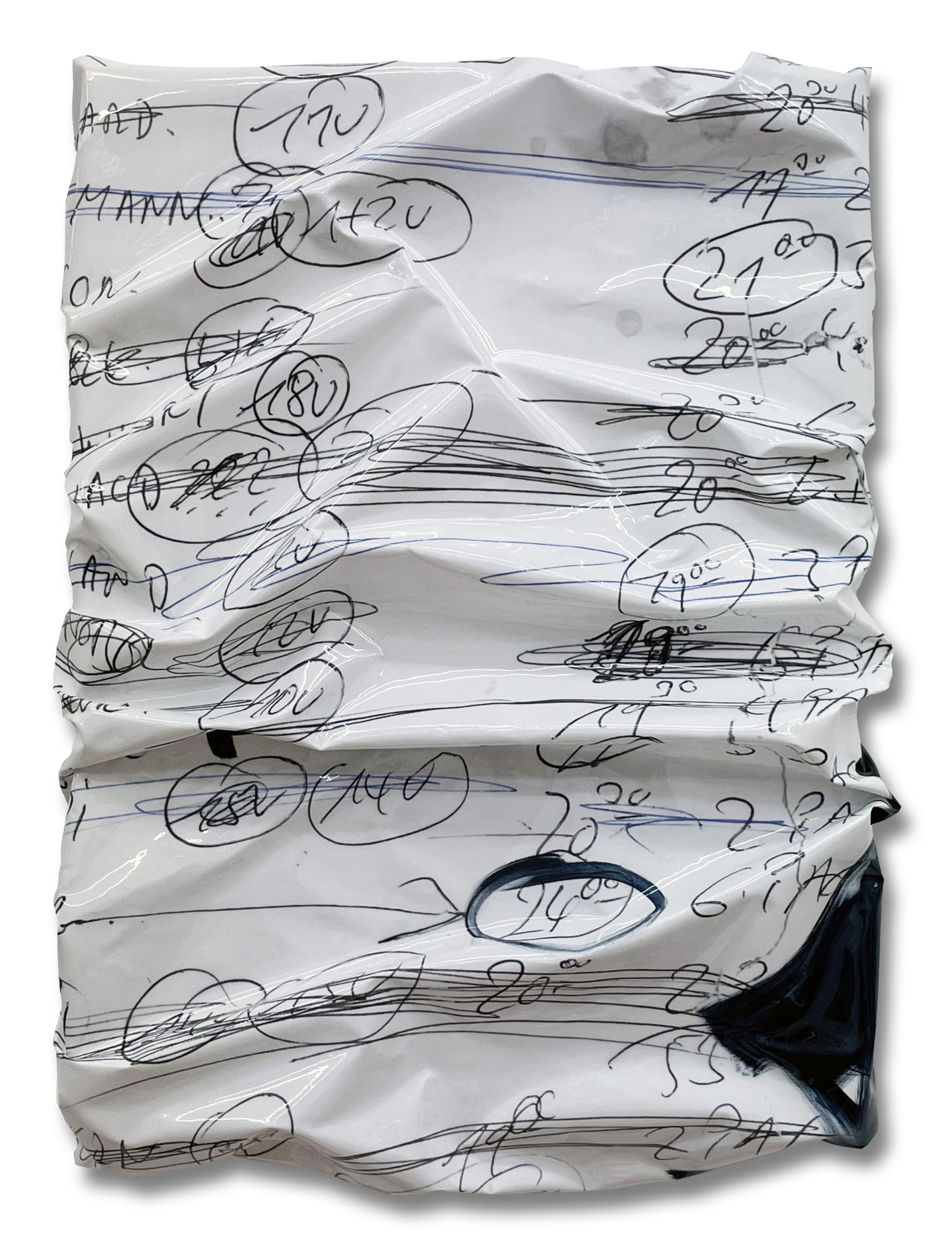

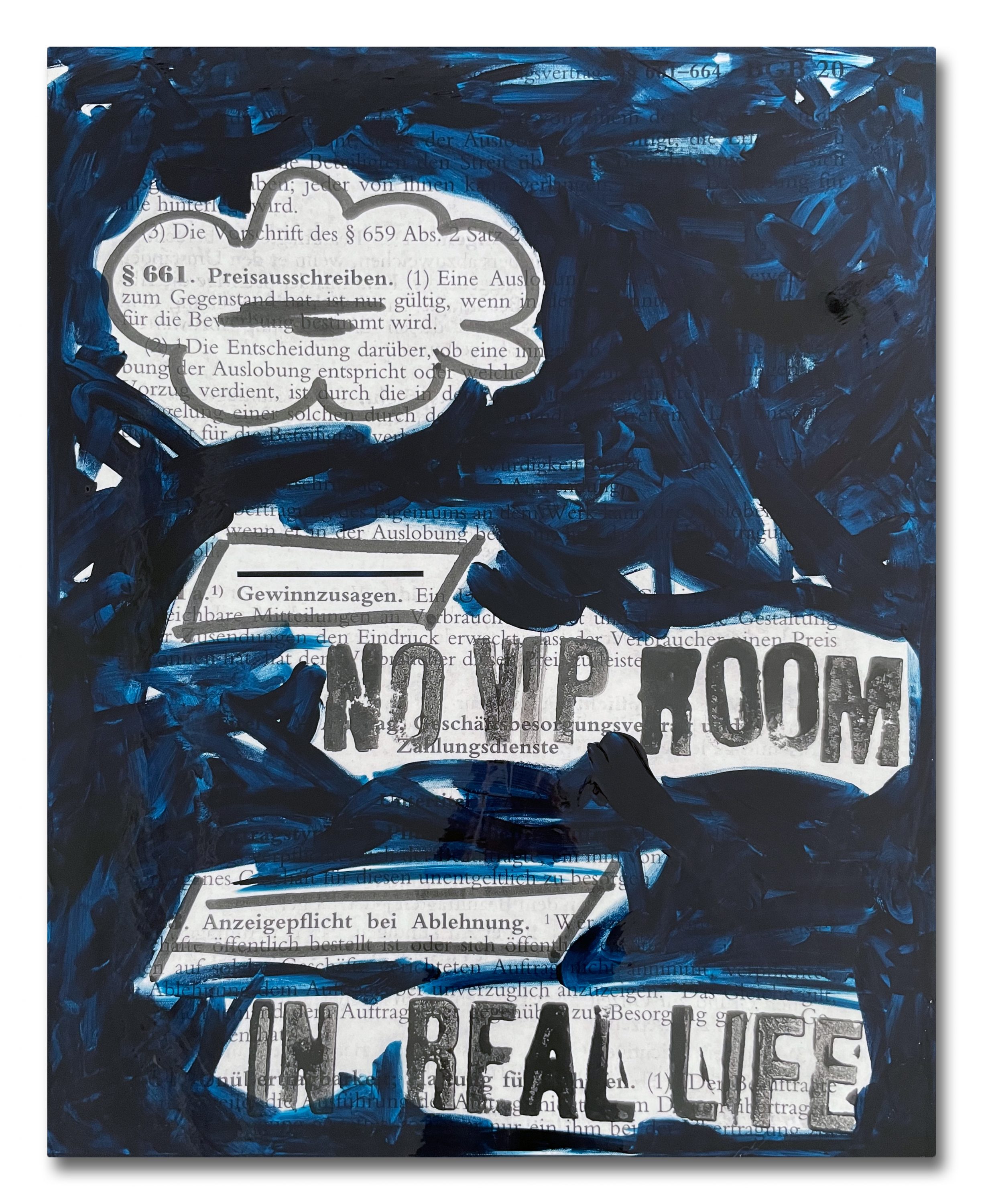

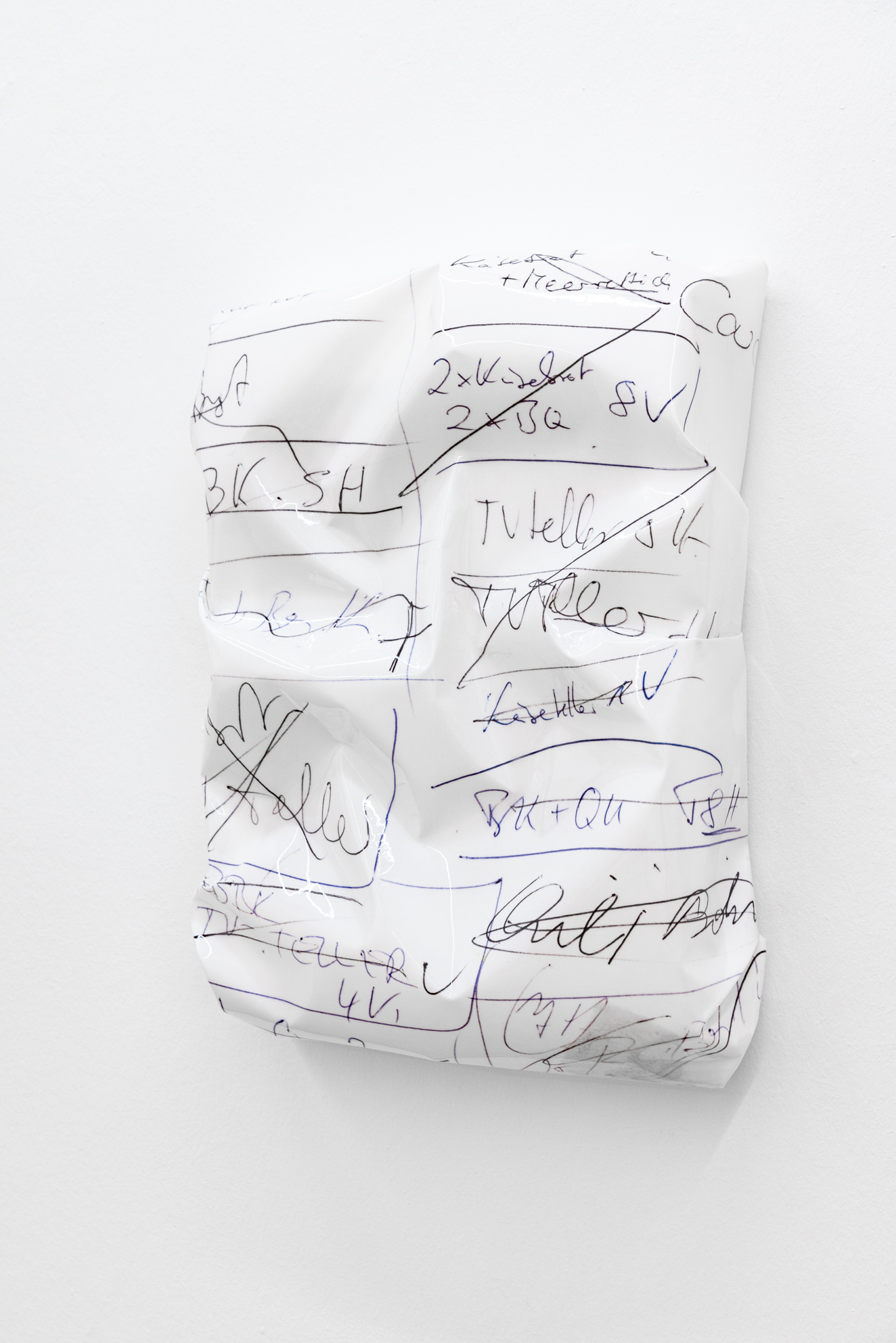

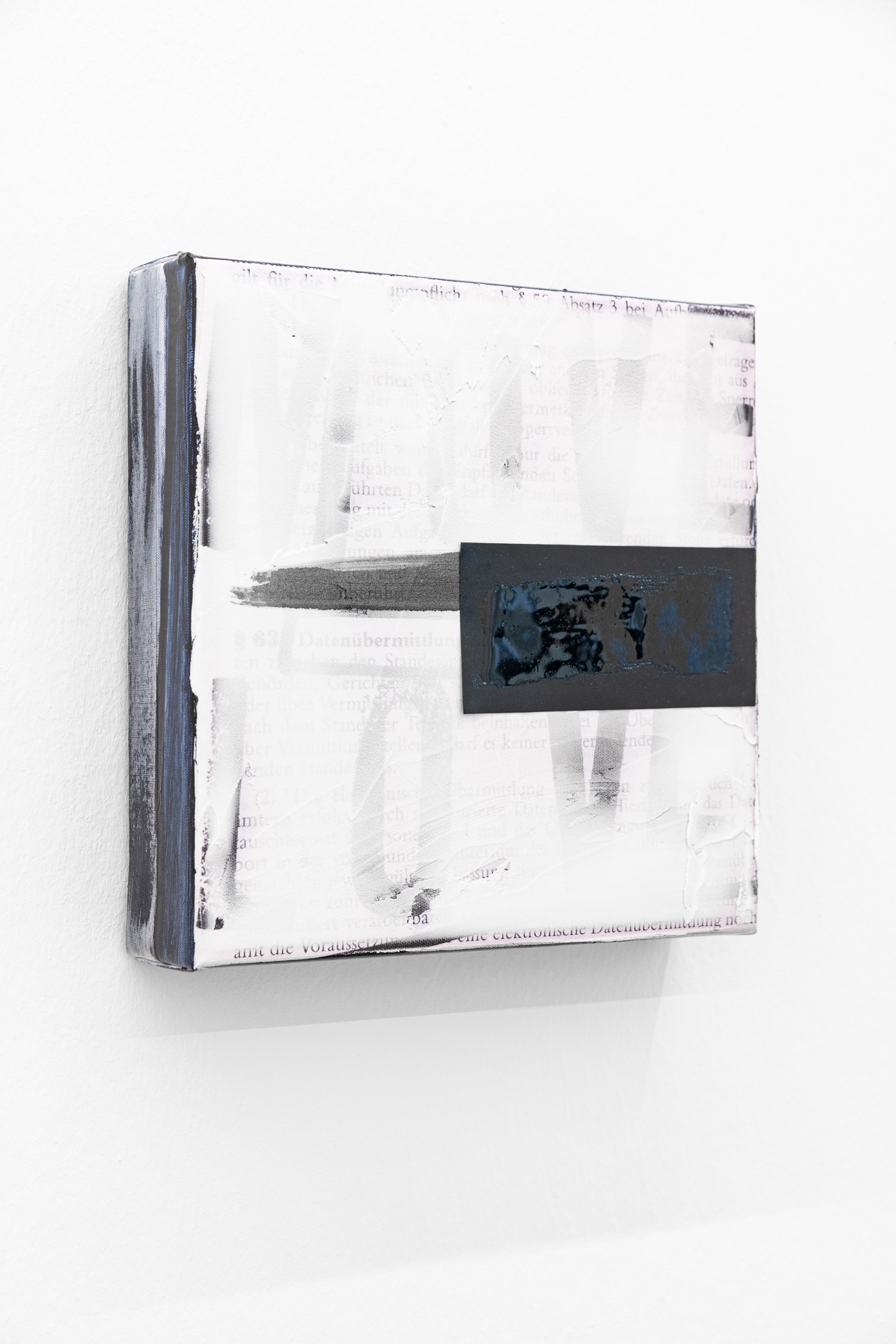

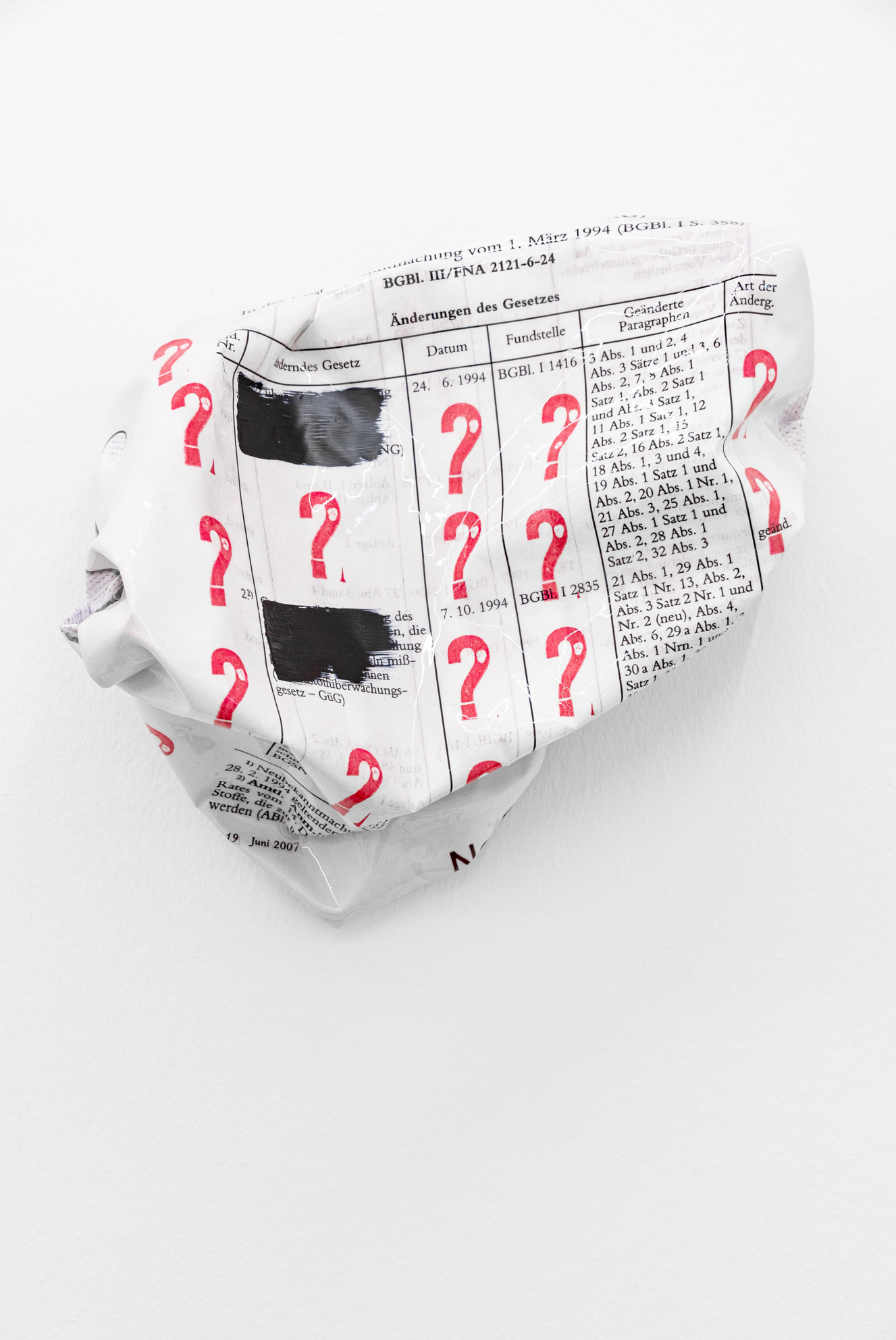

Before studying art in New York and Munich, Caro Jost studied law. The law with its requirements on action that shape the social, civic and political life continue to preoccupy the artist to this day. In 2016, she made over 500 drawings on original law sheets in her performative installation “Panama Paperworks,” which also served as wallpaper within the temporary office setting. The drawings resemble annotations that reflect the artist’s reading and interpretation through highlighting and deletions. In some places the sheets are stamped with her name or own terms. For a series of paintings, Jost printed a selection on canvas using screenprint, partly overpainted them, pasted them over and then poured over them with epoxy. Thus, in one of the works, in addition to individual fragments, only the terms “contest,” “prize promises,” and “duty to notify in the event of rejection” remain from the legal text. Stamped in capital letters on the work is “NO VIP ROOM IN REAL LIFE”. It is contradictions that come together here: the promising prize of a competition – an all-inclusive trip, perhaps – and the set of rules that brings disillusionment at the end. In another work, Jost uses a law sheet on the subject of change of family names. Much of it is crossed out, and the printed canvas is compressed on its carrier so that other things disappear into the folds of the canvas. On a piece of tape extending centrally across the canvas, we find Jost’s own handwriting, “Who travels to Las Vegas does not ask for the last name”. The clue this time leads to Jost’s own past and a spontaneous marriage in Las Vegas many years ago. Stamped on the bottom right of the work in capital letters is “CARO JOST.” The relationship has long since ended, but the name has remained as a trace of its own, inscribed in the artist’s work and identity.

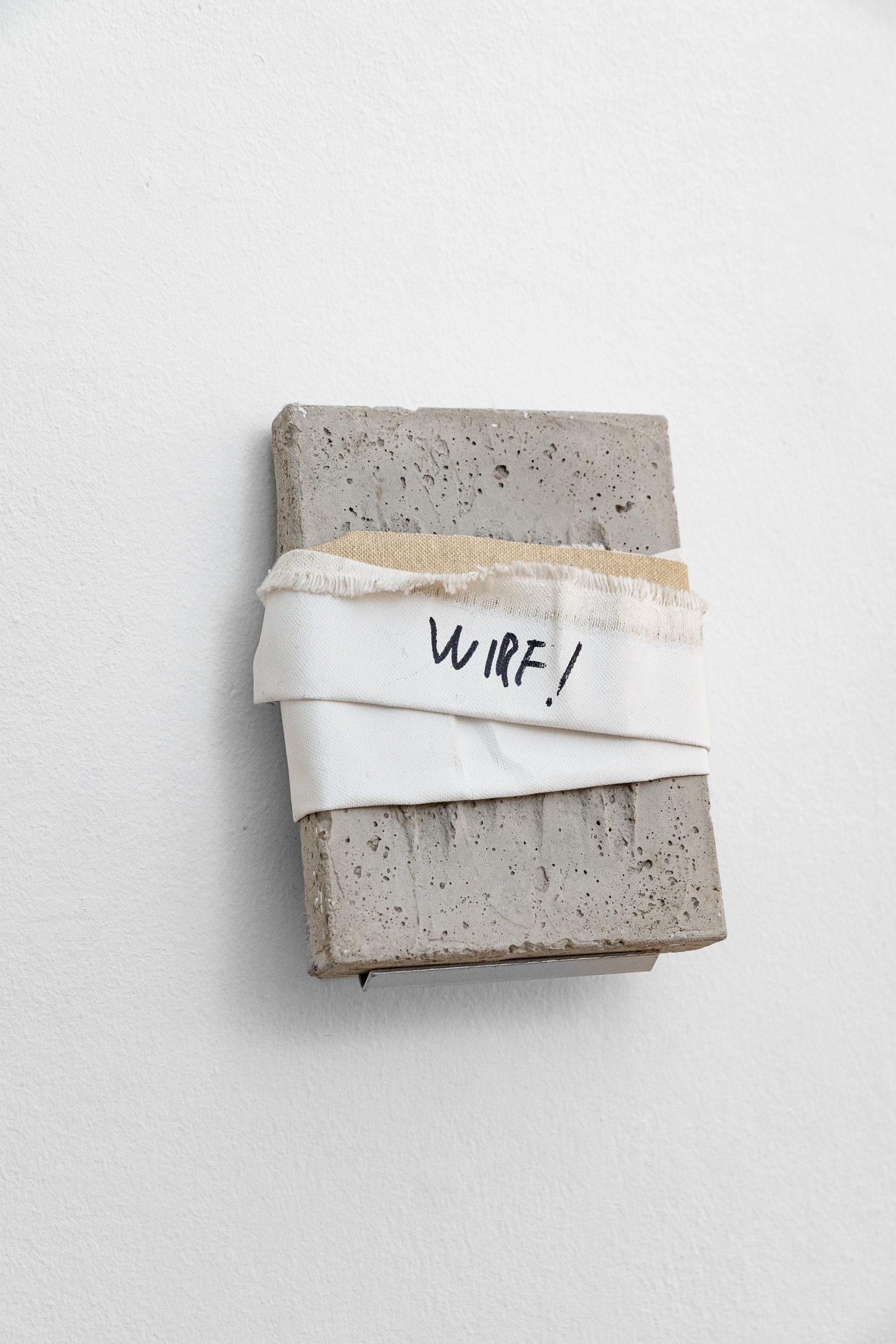

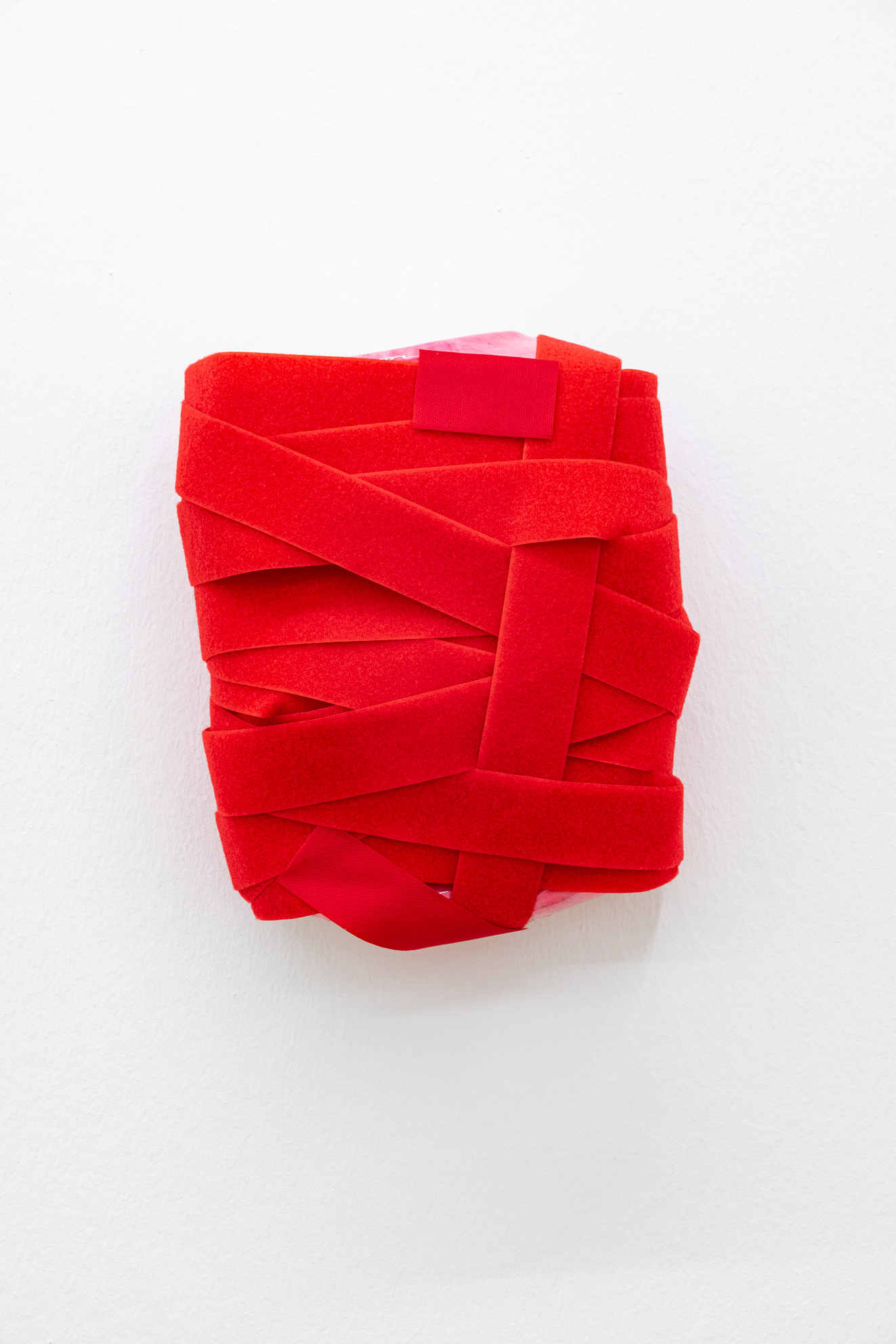

Caro Jost acts as an archivist who holds on to something and preserves it, who has an eye for the trivial, the humor in small things, the absurdity in others. In the exhibition at Britta Rettberg, in addition to the series of law paintings, the focus is on a work that was created ten years ago. It is a compact medium-sized canvas, which is completely wrapped with a black Velcro tape. The Velcro thereby seems to protectively cover something and hold this interior together. However, it also creates associations with confinement, the feeling of being tied down, and the need to loosen the Velcro. Jost shows the independent work in an installative setting for the exhibition, applied to a photo wallpaper: Caro at the beach. The aesthetics of the two layers are diametrically opposed. An image of a body and a body. It is the most personal exhibition she has ever done, Jost says in conversation. She is concerned with the public pressure of having to conform to a certain image, often especially as a woman, and to emerge from it. She uses confrontation, or rather superimposition, to ask the question, “Where do I reveal more?” The vacation picture on the beach is not. But the smooth mural, from whose superficiality everything seems to slip away, stands for the ideas of an optimization society, what a self-image should look like that we share, in which we communicate who we are. Jost counters this with her Velcro work, which here can no longer be interpreted in any other way than as a self-portrait or a description of one’s own state. A state that, by showing the work, has perhaps itself become a trace in the past.