Various Others 2023

In collaboration with blank projects, Cape Town

Time slips away, time passes. Time stands still, time stretches and condenses. To understand it as a linear quantity corresponds to the most widespread conception. It corresponds to the cultural practice of time measurement with clocks and calendars as well as a historiography in chronological order. Our subjective perception of time, however, is completely different: minutes can feel like a never-ending eternity and an hour can pass as quickly as the blink of an eye. Even the impression of timelessness is familiar to us, for example when we lose all sense of time while lost in thought.

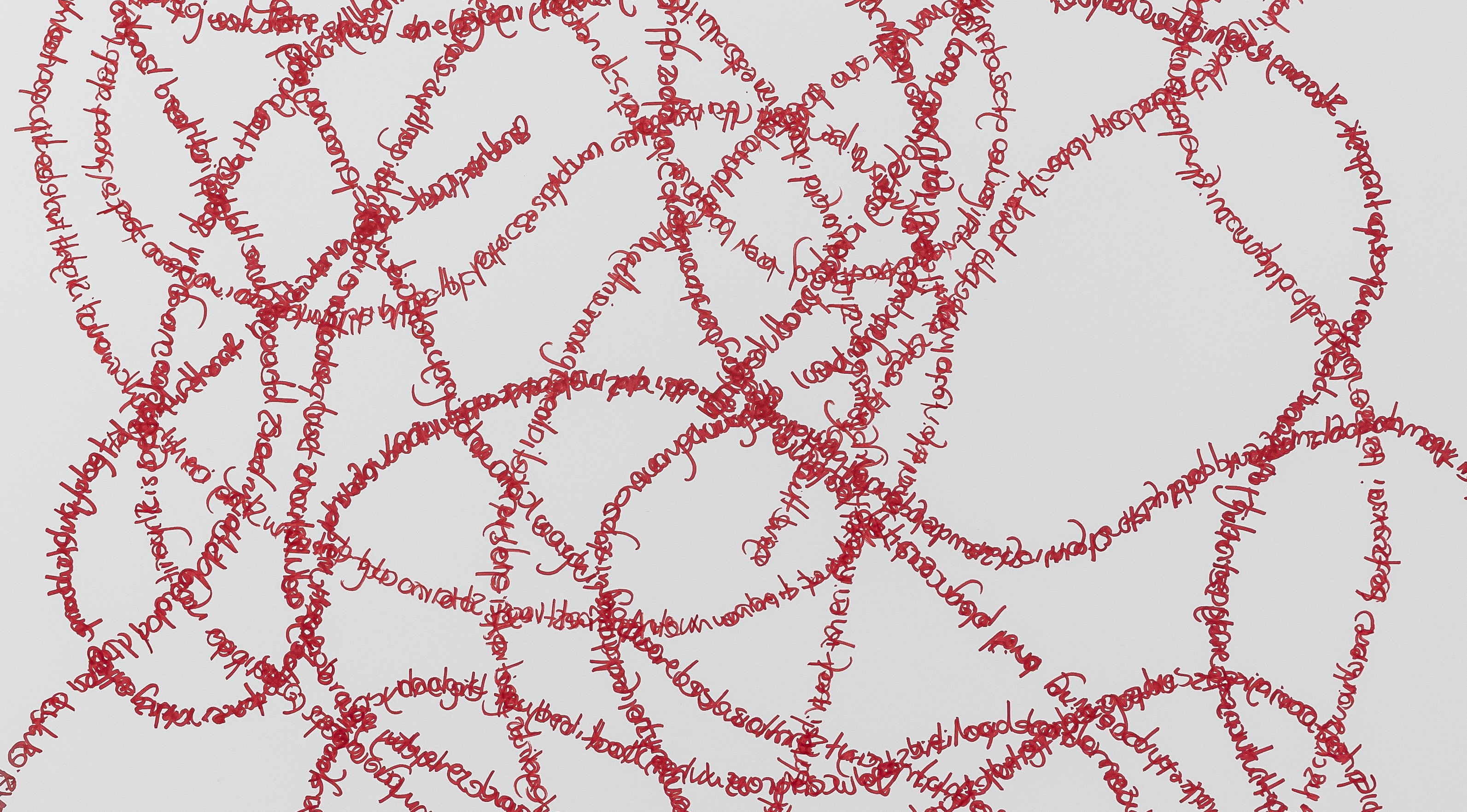

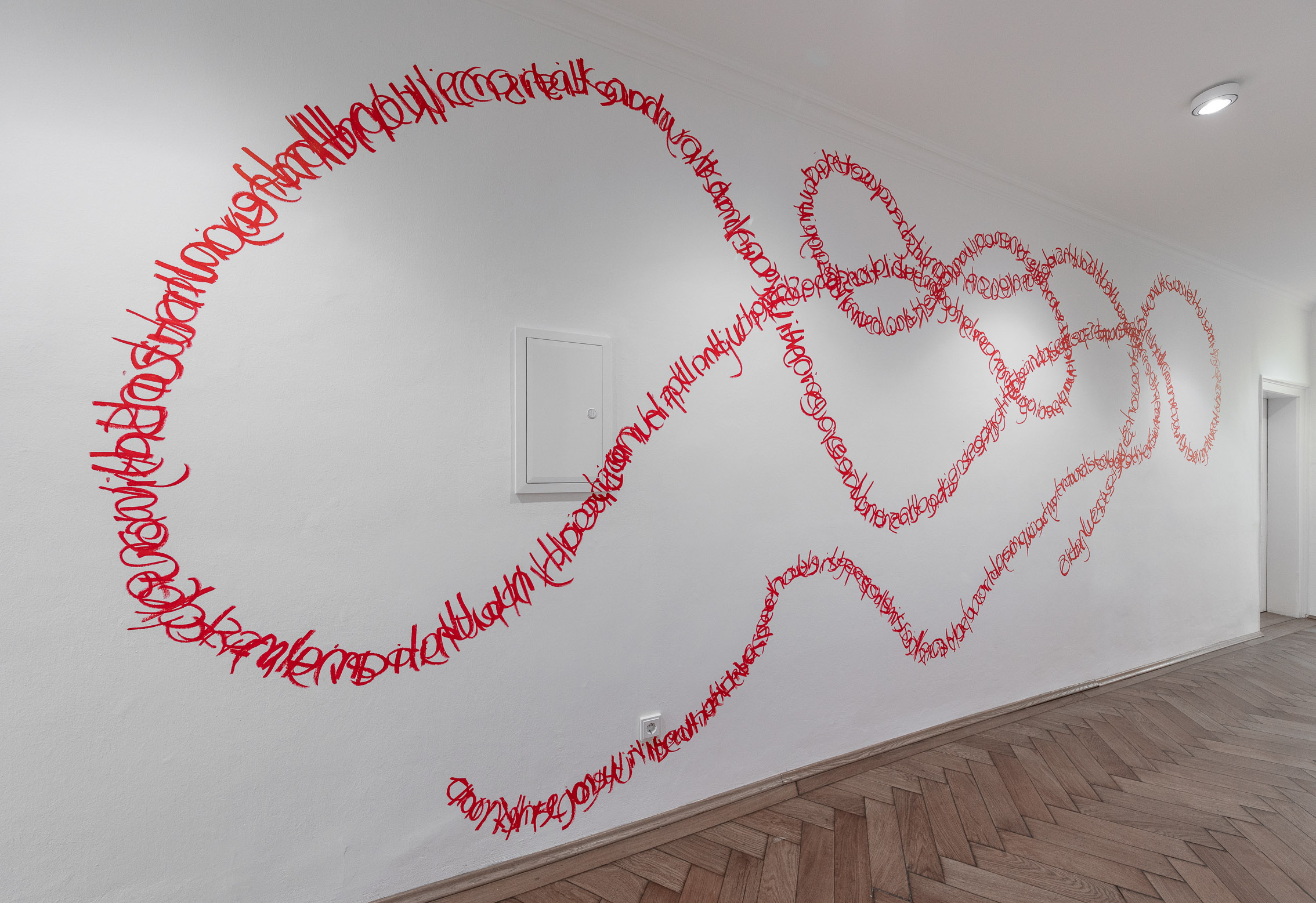

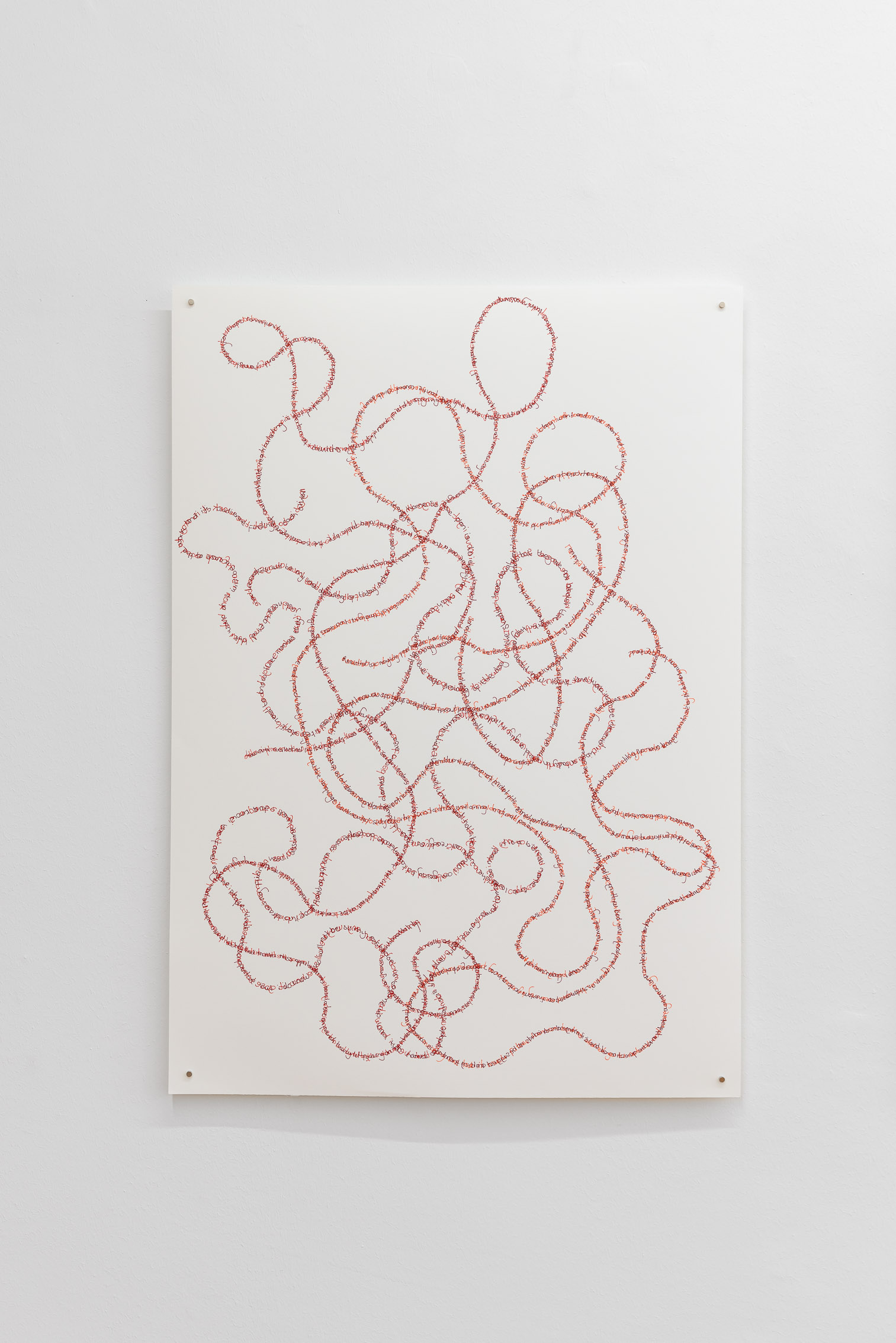

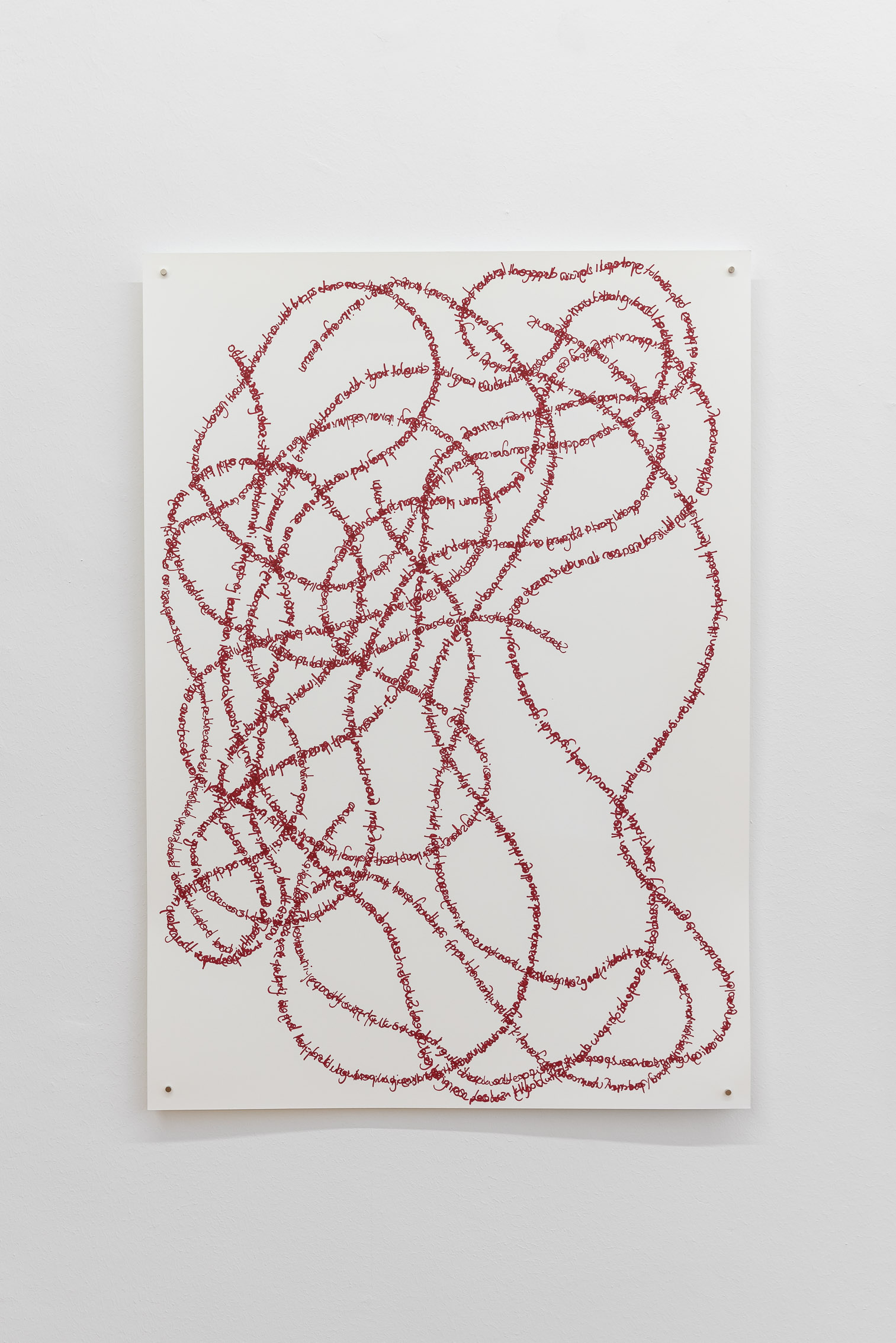

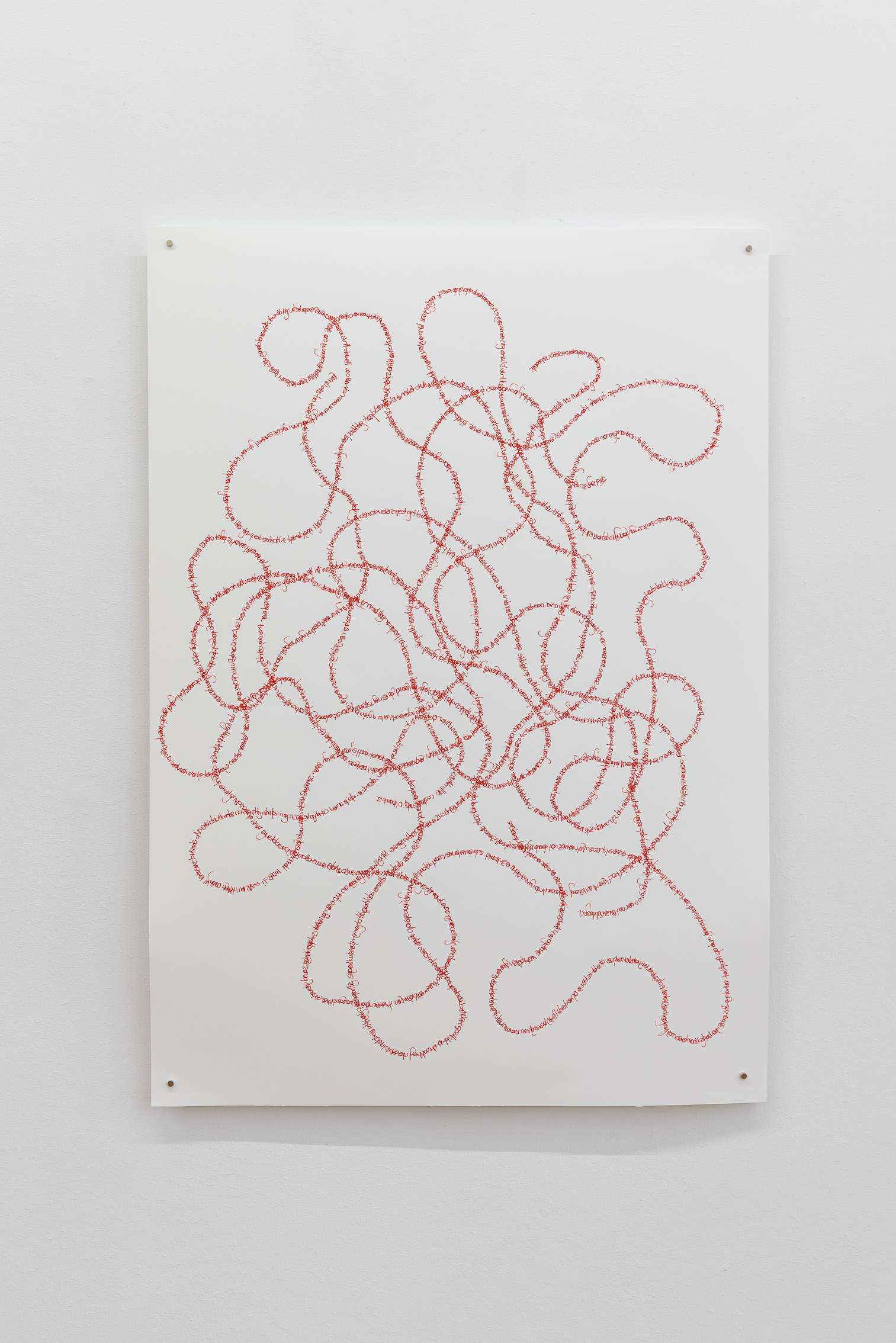

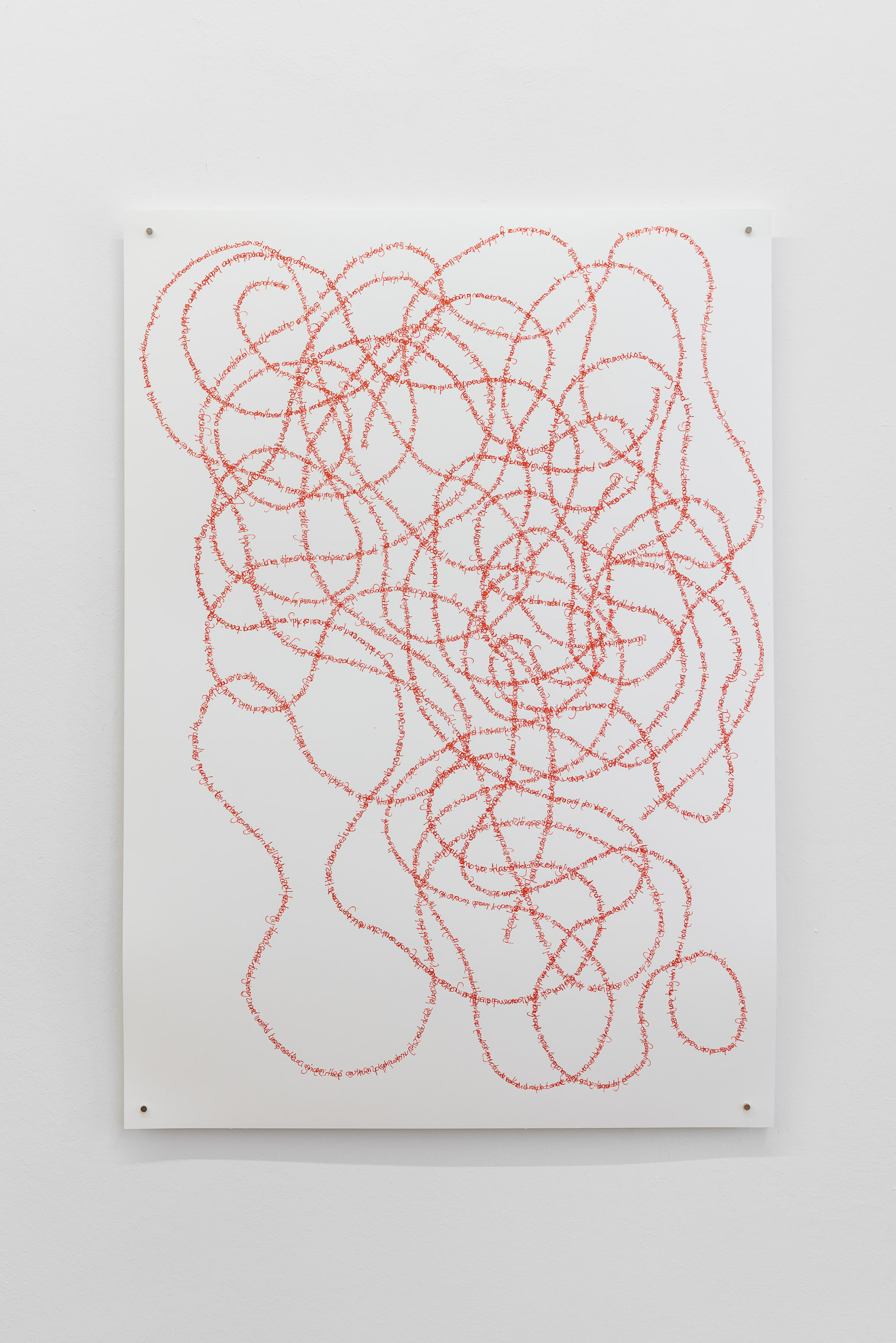

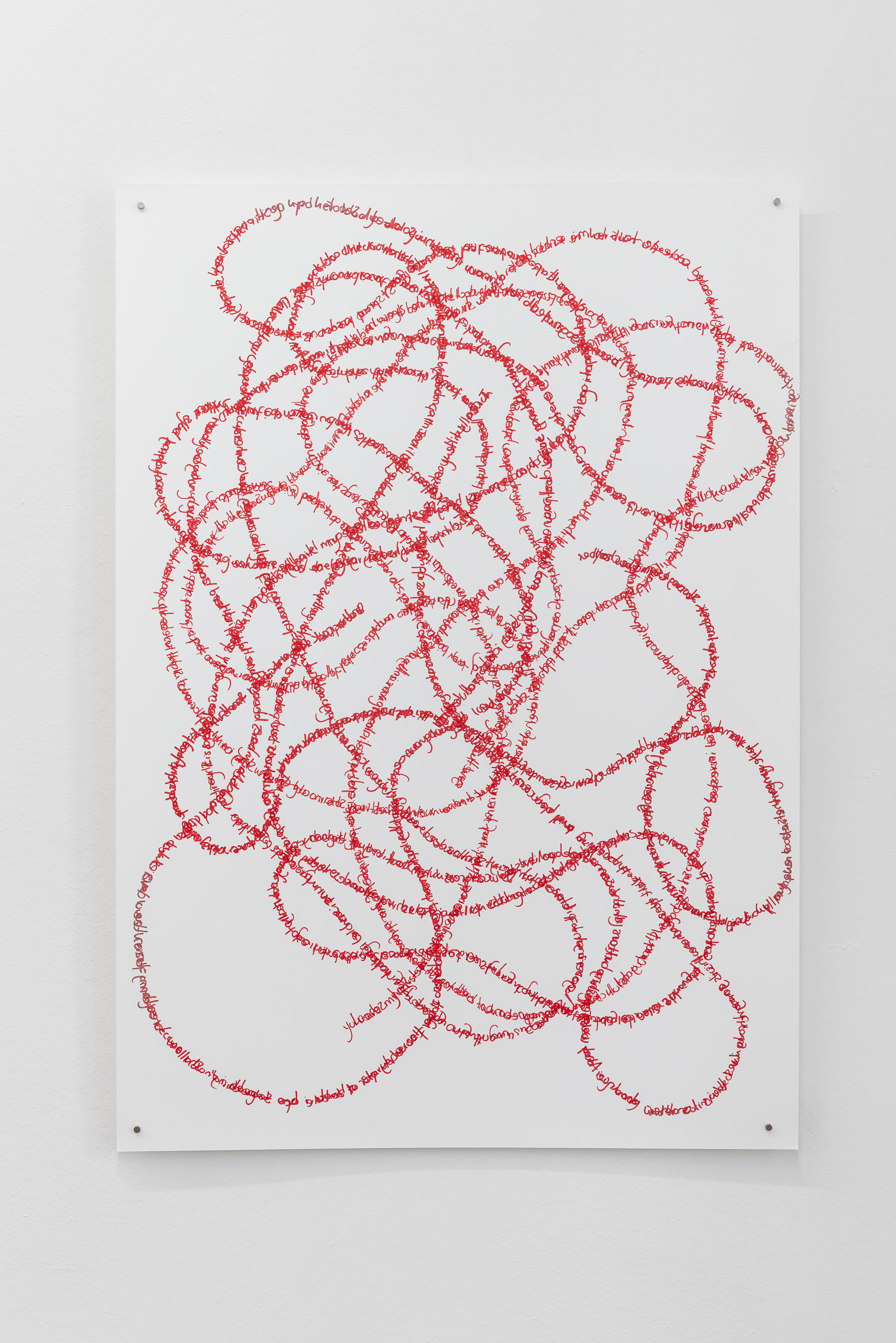

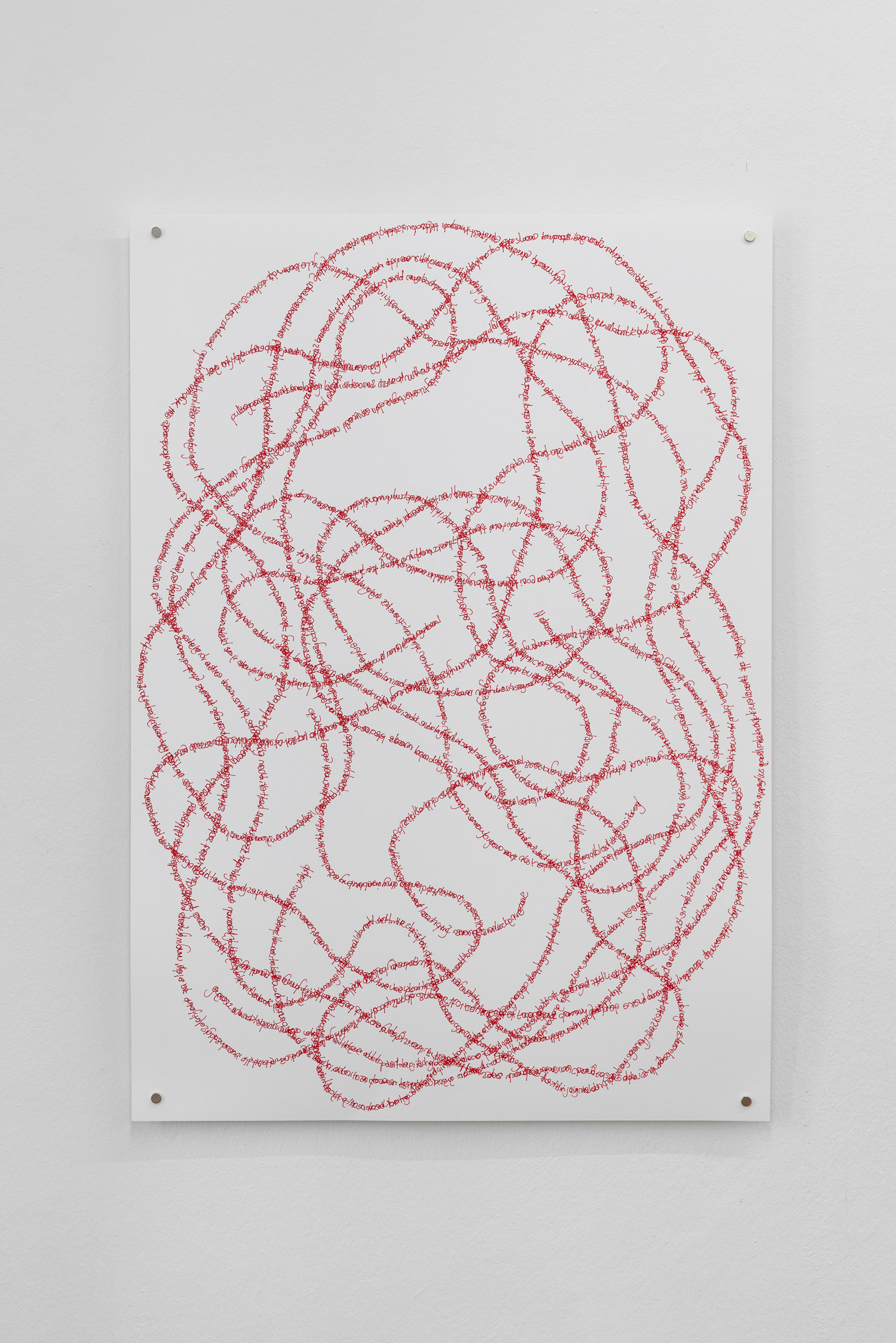

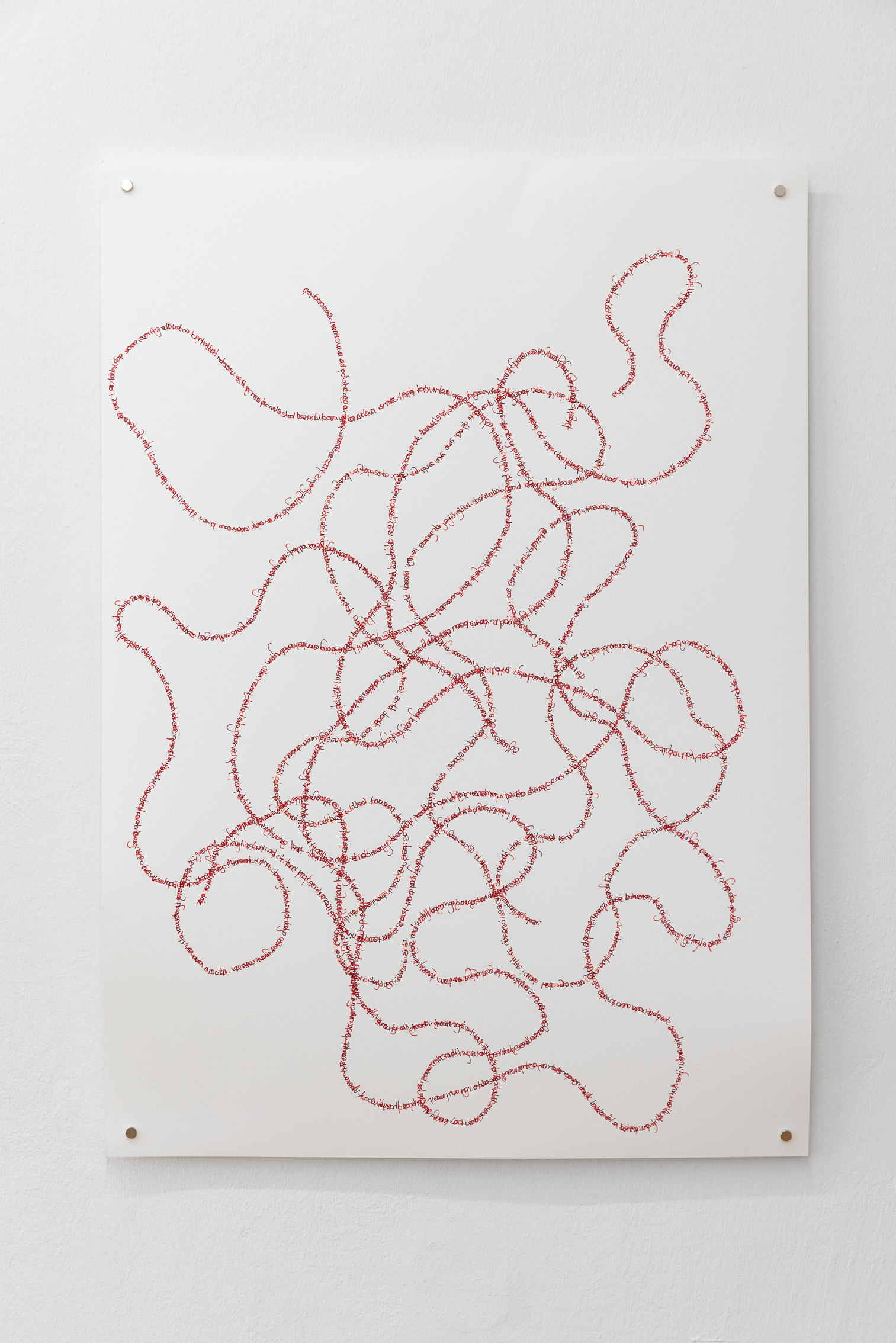

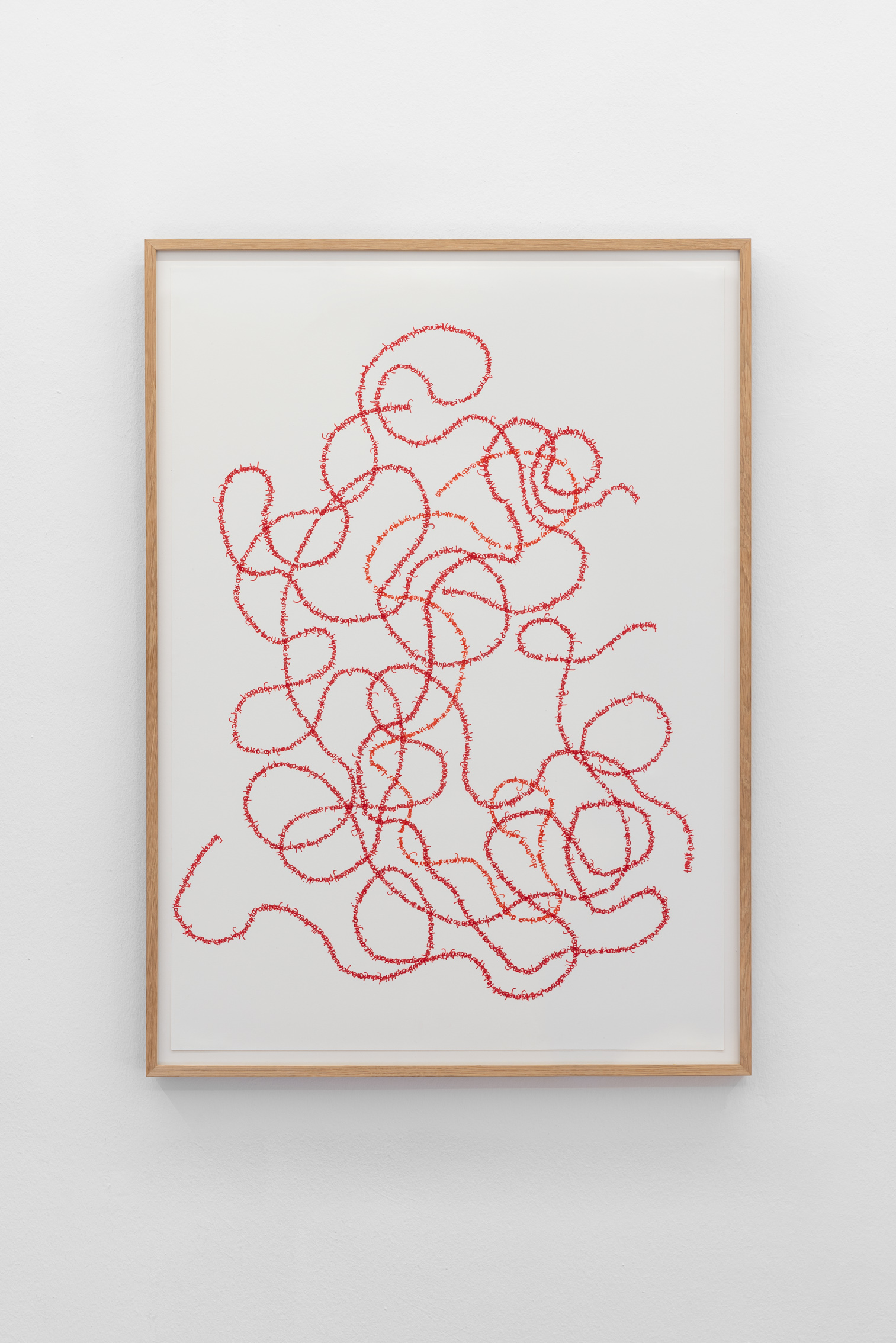

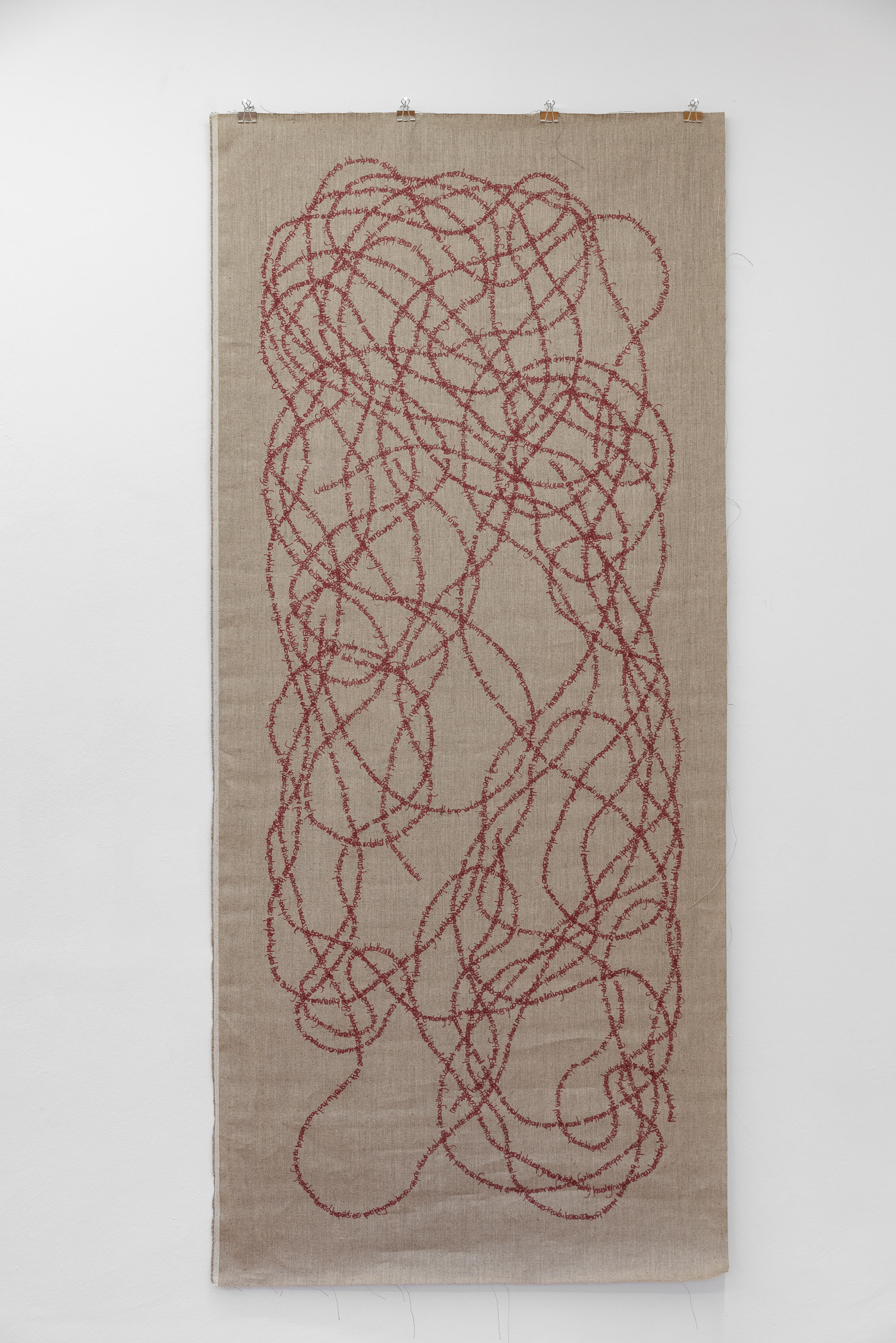

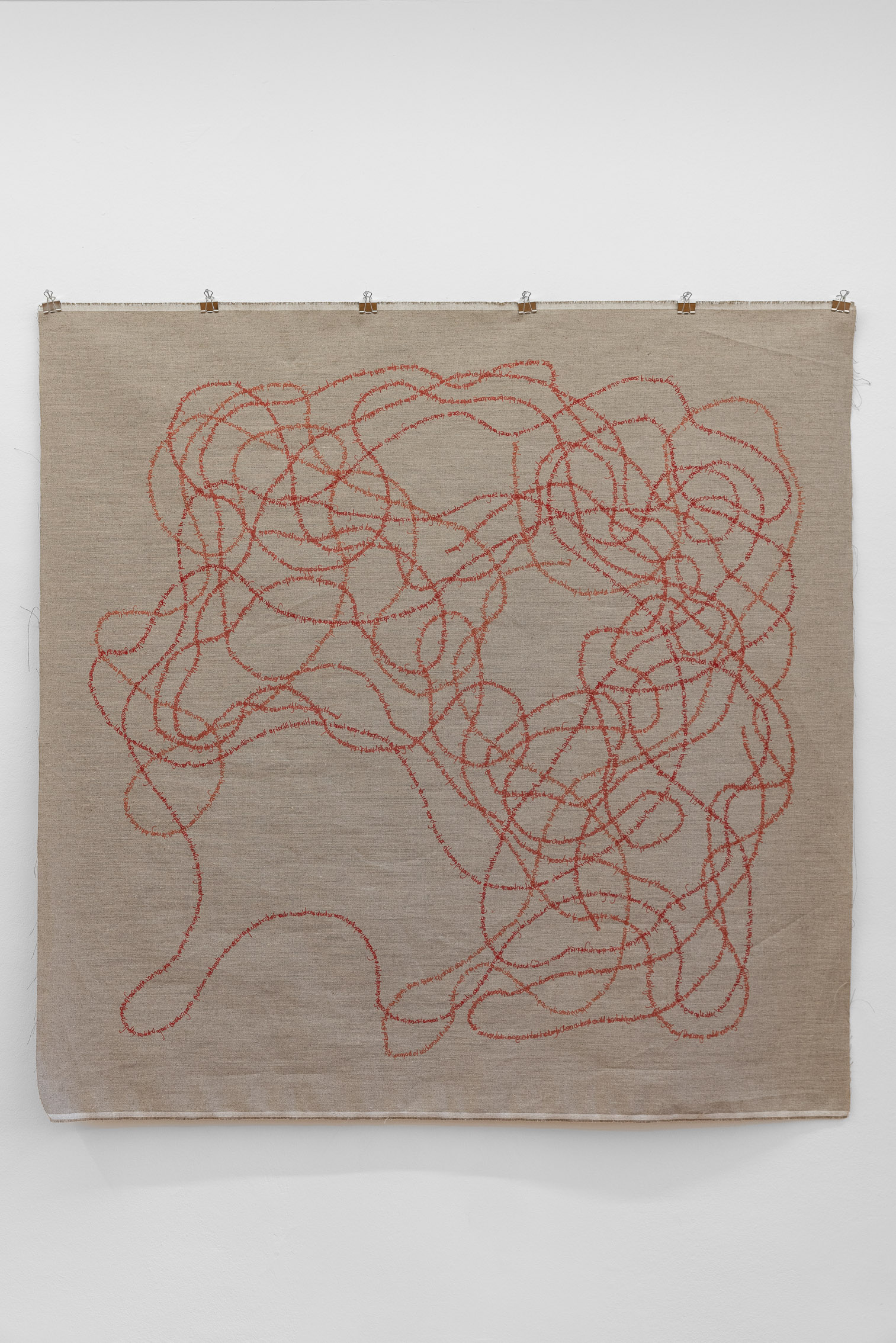

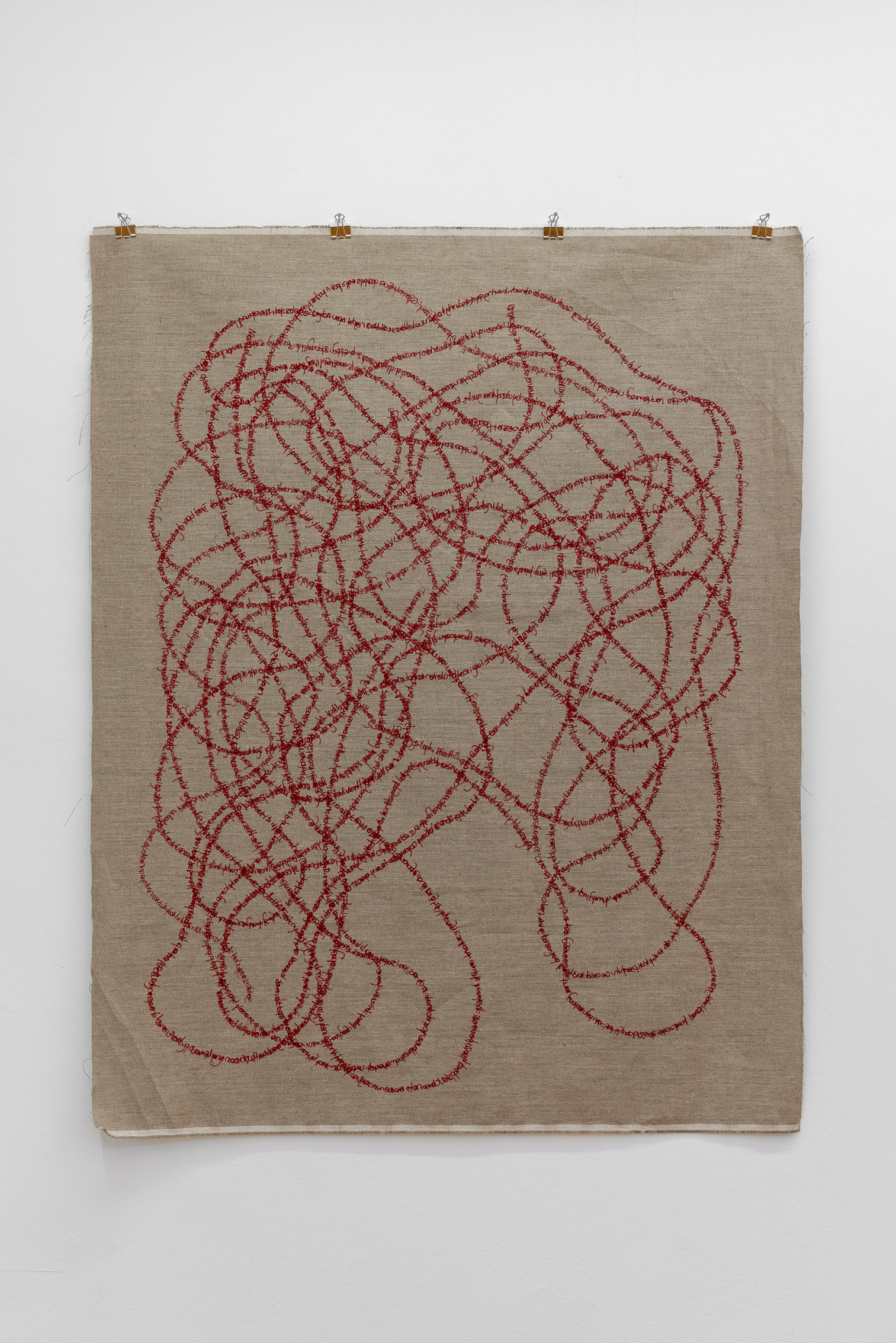

River of Thoughts – this is how Lerato Shadi has titled the series of her new works. At first glance, the river as a metaphor for the flow of our thoughts may correspond to an even and linear understanding of time. Looking at the new paintings, however, a different consciousness becomes clear. Meandering lines cross the canvases and sheets of paper. They turn out to be bands of writing that the artist applies directly to the picture surfaces with red markers – and which remain indecipherable to us. Her writing technique is based on overlapping characters: After the artist has applied the letters in learned writing from left to right, she mirrors the writing and traces it again in reverse form and direction on the same writing track. The bands of letters draw circles and loops, they cross each other, concentrate in some places, while other areas remain largely blank. Doesn’t this offer a completely different approach to time than that of a linear flow?

In a cyclical conception of time, the recurring moment becomes more important than the passing one. Every morning the sun rises again, the seasons return in the same order, and every low tide is followed by a high tide. Much of nature is organized in cycles, including aspects of our bodies and being human itself. Our story, however, we usually try to tell in a linear manner. In her paintings, Lerato Shadi creates a different form that argues for leaving the path of linear narratives. While writing, here conceived as a performative act, the artist continually moves around the picture surface, changing the direction of looking and writing. Concepts such as beginning or end become less important here, while perspective plays an increasingly important role. Different strands intersect and in some places form condensations, like a song that swells and then subsides. Then again empty spaces, like undescribed fields of the earth’s history or a silence around what has long been forgotten or concealed. Several loose beginnings and endings can be found on the surface. A canon has not only one beginning, but many – and it can be sung endlessly. It is the circular song. Tsela di Matlapa is what Lerato Shadi called this exhibition, after a South African folk song that was often sung in her family. Translated, it would mean something like “It’s a hard road,” but that plays as minor a role as the content of that writing, which is no longer legible. Even before we can understand the meaning of lyrics, and even if it never fully reveals itself to us: The melody, as well as the way of singing, transports its own level of meaning, which remains independent of semantics.

Each line of writing that Lerato Shadi has applied to the picture surface here, she has rewritten a second time – mirrored and backwards. The idea of revising histories – and history in particular – is not new, but it remains virulent. Only slowly is an awareness emerging in the broader social field to question narratives in terms of their narrative perspective. From whose point of view are history books written? Whose history is told there, and from what point of view? Who writes and who is merely described, who acts and who is merely treated? And who is missing? Lerato Shadi here also raises a critique of the written form as a strategy for conveying knowledge and history. Texts have their pitfalls: once written down, they always detach themselves a bit from their authorship. In a field that claims neutrality and strives for objectivity, this circumstance is problematic: a text always remains a subjective account. An awareness of this is the prerequisite for critical reading and, consequently, for independent thinking and reasoning.

Her video work Mabogo Dinku, which can also be seen here, focuses on a different form of expression. With her hands, the artist forms gestures, accompanied by the singing of a South African folk song. Some gestures are universally understandable, others leave room for different interpretations. The screen splits, and the visible hands seem to react to each other. A plot unfolds, and it remains open whether one’s interpretation of the gestures corresponds to the narrative intended by the artist. Neither the title of the work nor the song are translated by her into English or into any other language dominant in Europe. What can also be read as a commentary on the marginalization of the South African language during the apartheid regime (and beyond) is at the same time a universal reference to the peculiarity of culture and language, which goes far beyond the written and purely lexical. A language is characterized by certain images, by its own metaphors and allegories, which have been culturally formed over a long period of time and are primarily passed on orally, in stories and songs. If a foreign language becomes primary, more than just a vocabulary gets lost.

In the overwriting of letters, in rethreading backwards what has already been written, the attempt to revision becomes apparent. Can we walk back along the path of what has been handed down and reevaluate what has happened? Can we add new narratives – or at least new perspectives – to the stories? The idea of “unlearning” is a notion that is currently relevant for good reasons. It means the conscious unlearning of internalized structures, hierarchies and patterns of action. This unlearning is preceded by intensive awareness: What norms have we learned, what behavior have we been taught, and what conventions do we unconsciously follow? These questions arise with regard to our own personality as well as for entire societies. Unlearning is not the same as forgetting. Perhaps it is even the opposite.