The Rite of Spring, the fourth and longest segment of Disney’s Fantasia, opens with its silhouetted conductor, Leopold Stokowski, framed in purple-blue light and gesturing into blackness, out of which arises a cosmological sequencing of The Big Bang. The moving pictures that follow narrate a fantastical rendition of the universe’s expansion, but one that is enveloped by the conducting arms of Stokowski as he urges forward the building energy of Igor Stravinsky’s composition. Volcanic eruptions, microscopic amoeba, ambisexual sea creatures and fighting dinosaurs. ‘Natural History’ is orchestrated along a rising and falling rhythm of creation and extinction, captured and defined through an anthropocentric, capitalist-cartoon lens of linearity and classification. Stokowski’s gestures hold within their movement the omnipresence of an invisible creator, the owner of this version and vision of space and time – our ‘Natural History’

In one room of Frances Drayson’s exhibition at Galerie Britta Rettberg, carbon-rendered apparitions of dinosaur forms are willed into being through meticulous depictions of bone and tissue. Interlinking geometries hover on the surface of the paper, surrounded by the smoky smudges of residual carbon. These bodies have names – ‘Donna’, ‘Jackie, ‘Lucille’, ‘Nancy’, ‘Pattie’ and ‘Sandie’ (all 2021). They could have been named after the quarry sites in which they were found or after the landowner who owns their sedimentary grave, but as the printed map found in the exhibition speaks of: ‘the sex of the body is unknown, so in keeping with tradition here (boats, cars and so on) she’s regarded as female’. These lifeforms are containers of memory; they represent a visceral and intricate compression of time that stretches beyond the minute cerebral capacities of the human brain and its colonising desire. And yet their discovery requires classification (species, gender, lineage etc.) in order to be recognised and made visible. Drayson allows their messiness to remain.

The human impetus to synchronise and regulate the nonsensical, the chaotic, and the disordered, is not only predicated on a desire for control, but often it is a mere coping mechanism in response to the fact that our everyday lives are wedded to and measured through a coordinated tempo of linear progression grounded in sensations of velocity and overwhelm. Labour, family and play are all bound together in this goal-oriented movement that is shaped and dictated by the mechanism of a white-patriarchal-heterosexual-capitalist paradigm. Each of the layers that make up our everyday experience is thus driven by a concerted dissemination, reinforcement and cultivation of certain narratives, identities and codes. When you dig a little deeper, it seems that the power structures and systems that classify dinosaurs in a natural history museum exist on a temporal continuum with the multiple ways that our human subjectivities are divided and defined through legal, socio-political, and biological frameworks. We are but animals trying (or not trying) to resist our own insignificance and the relentless potential of our own disappearance.

In searching for new modes of classification, Drayson’s work speaks to this desire to resist the systemic structures that underpin our lives, bringing forward the psychological processes that could provide us with temporary escape routes. The cartographic panels of “Plot of Land III” (2021) are vectorised renderings of the artist’s grandmother’s drawing of continents and supercontinents. Shifting from a defined tracing of existing topographies to a more freehand unwieldiness, the doubled lines carve out a spatial pathway across the surface of lubricated MDF sheets, while mapping the temporal movement of their author. What emerges is the instability of these geographic formations and their perpetual re-creation across time. Michel Serres writes that ‘time does not always flow according to a line, nor according to a plan but, rather according to an extraordinary complex mixture, as though it reflected stopping points, ruptures, deep wells, chimneys or thunderous accelerations…a visible disorder’.[1] The development of history might then resemble what chaos theory describes: a disorder that represents the coalescence of temporal frames – past, present and future – blending in an amorphous complexity belying patterns, interconnectedness, repetitions and multiple feedback loops. It is within the ‘visible disorder’ of Drayson’s plotted maps, or the clustered composition of the waxed bronze sculptures that sit alongside the carbon dinosaurs, that a more idiosyncratic rhythm can emerge.

The truth is that temporal experience is as uncategorisable as the messy reality of cutting open a body and trying to identify each organ. We are constantly at the service of a scientific and legal diagrammatic imaging of time and space that arranges our reality through a controlling and often violent linear determinism. But just as we may be aware of these encroaching forces within our brief lives, the histories of human behaviour are embedded with a recurring desire to enact a similar level of dominance over other non-human lifeforms. The movement of livestock is abstractly referred to in the sculpture “If you cannot keep a rhythm how will you know when you are next fed? (for Dieter)” (2019) through the motif of the cattle grid rendered in polymer plaster, pinched and crimped by the artist’s hand. The grid is a minimal piece of agricultural furniture that inhibits and controls movement. In rotational grazing, cows are frequently moved from one field to the next in order to reduce grass wastage and deterioration, leading to ‘greater grass utilisation, improved pasture quality and greater grass yield’.[2] This structuring of each cow’s existence through its cyclical movement around fields over the course of a day speaks to the basic monotony with which their time is managed in line with the rise and fall of the sun, quantified and optimised for maximum productivity. Following Paolo Virno’s definition of human capital, these are labouring bodies that are both a productive force, but also the product– just like us. Think of the commuter herds at train stations every morning, conducted through barriers, slipping into autopilot. Think of the Honey Ant referred to in Drayson’s eponymous sculpture, clinging to the roof of their nest as a swollen larder for the rest of the workers. We cannot escape the fact that we are simultaneously the producers, the produced and the product itself.

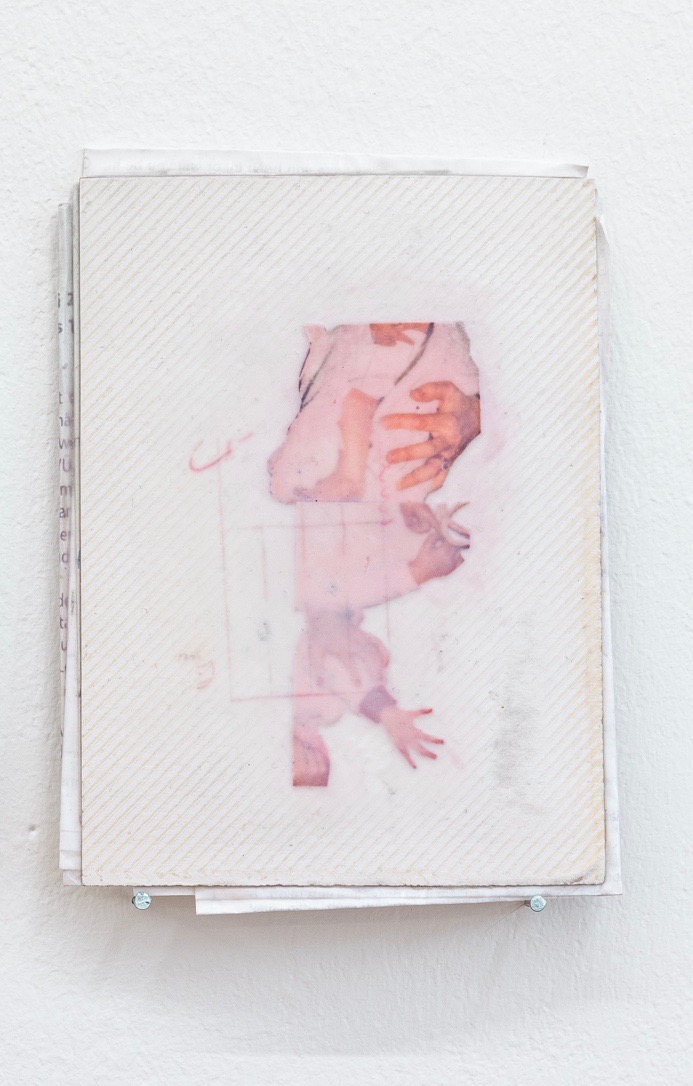

Anonymity, facelessness, depersonalisation. It is often through such strategies that the management of human bodies is made bearable for those that enact it. The profiling of individuals based on sex, race, age etc., is dependent upon a concomitant subtraction of selfhood so that they might fit within certain structures that can be monitored and consumed. And who are the corporate dinosaurs that disseminate and uphold these legal and socio-political frameworks? In Drayson’s series of small collages, personal images from childhood are layered on top of photo album backing boards that cover a compressed sandwich of various legal documents relating to the death of a family member. Courts, tax, insurance, and so on; subjects that are brimming with a jargon and linguistic coldness that is wholly divorced from the language of kinship. They are documents that require their reader to play the amateur detective, a perverse narrative of extraction and deciphering that Drayson subtly refers to through the titles of each work.

From The Big Bang to quotidian kinship. This expanse of time stretches out in a complex constellation that can be at once deep, unruly, banal, bureaucratic, joyous and violent in its texture. Drayson draws our attention to this idiosyncrasy, engendering a mode of dissent from the temporal and spatial binds that mediate our lives, and the classifications that seek to define us. ‘History…is notable for its failure to address the question of the ontological, epistemic and political status of time’, writes Elizabeth Grosz.[3] It is within this failure that the traces of alternative spheres of existence can be identified, resisting and rejecting the coercive energy of the conductor.

[1] Michel Serres and Bruno Latour, extracts from Conversations on Science, Culture and Time, trans. Roxanne Lapidus (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1995), 56.

[2] ‘New Entrants to Farming: Rotational Grazing’, Farm Advisory Service

[3] Elizabeth Grosz, Becomings: Explorations in Time, Memory and Future (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 2.

Joseph Constable is a curator, writer and producer. Formerly Associate Curator at the Serpentine Galleries in London he is now Acting Head of Exhibitions at the De La Warr Pavilion, Sussex.